Cancer: The Emperor of all Maladies. For decades, scientists from all disciplines have dedicated their careers in hopes of defeating this insidious disease. Unfortunately, these efforts have not yielded effective long-term solutions for battling cancer and its vengeful relapses.

This paper titled ‘Bacterial survival strategies suggest rethinking cancer cooperativity’ suggests a fresh outlook on cancer by drawing multiple parallels between tumours and bacterial colonies. According to the writers, a more communal-oriented research approach is necessary if one wants to truly understand the dynamics of cancer. What better way to do this other than comparing it with one of nature’s most thriving communities?

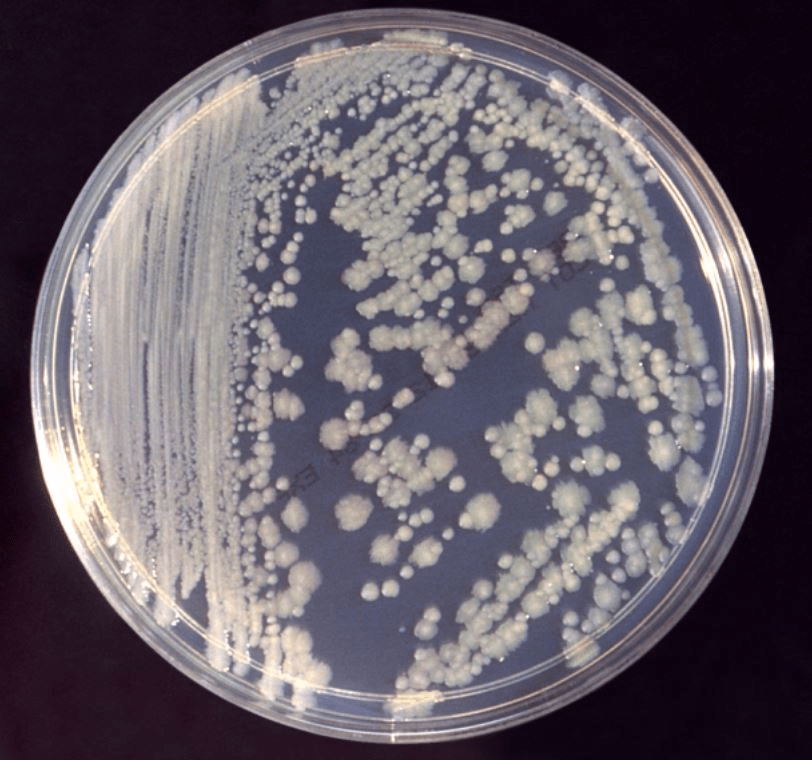

Bacteria form highly complex societies comprising of multiple sub-clonal populations each dedicated to serving specific purposes for the benefit of the colony as a whole. For example, ‘persister cells’ serve as latent juggernauts whenever the colony is subjected to harsh conditions. They survive through lethal antibiotic doses and enable the revival of the bacterial colony once the conditions become optimal. ‘Competent cells’ sample the available plethora of genetic variability and select traits that are best suited for survivability. Once the mother colony is established, search parties are sent out to explore other regions of the local environment to find more colonization opportunities. These search parties and colonies remain in constant communication with the mother colony through chemical signals or by utilising the information brought back by the migrating bacteria.

An exciting example of this is the way in which the population as a whole deals with stress factors such as antibiotics. If an antibiotic is detected in one of the secondary colonies, a message is sent to the mother colony which results in a troop of antibiotic resistant bacteria being sent to the secondary colony in order to ensure its survival.

Cancer shows multiple similarities with bacteria in terms of its social interactions. Since it is capable of extreme proliferation, it too has multiple subpopulations with phenotypic variability. The primary tumour sends CTCs (Circulating Tumour Cells) in search of new locations for colonization. The process of cancer spreading from the primary tumour is termed as metastasis which is responsible for 90% of cancer deaths. These CTCs then form colonies and remain in constant communication with the primary tumour. They send cells back to the colony which then reintegrate with the mother colony in a process termed ‘self-seeding’ which has been shown to increase cancer growth. These self-seeding cells bring back valuable information that the primary tumour utilizes to prepare future CTCs with proper traits to ensure their survival in the paths that they encounter.

The way cancer becomes dormant and relapses is very similar to bacterial sporulation. When bacteria are subjected to extreme conditions like antibiotics, they form spores and become dormant until conditions become favourable again. Surprisingly, the germinated form of these bacteria is now resistant to the antibiotic stress. Similarly, cancer relapses result in treatment-resistant tumours. Although the individual decision of cells to become dormant might be stochastic, it is controlled on a population basis.

Another impressive feature of cancer is its ability to enslave surrounding cells and use them to its advantage. It is even capable of tricking the immune system and in certain cases, uses the immune system to promote its growth!

The most exciting part of this paper was the writers’ explanation for the resemblances cancer has with bacteria. How is it possible for eukaryotes to display such striking similarities with prokaryotes? To answer this, we must first understand that cancer is the result of breakdown of multiple regulatory systems that characterize a eukaryotic cell. Thus, in effect, the cells lose their eukaryotic nature and fall back to their ancient prokaryotic heritage. It is almost an atavistic return of primal survival strategies.

As is illustrated above, tumours are not simple cohorts of uncontrolled cells without a leash. Instead, they are highly structured societies with complex architecture that behave almost like individual organisms, much like bacteria. Therefore the best way to defeat cancer would be to disrupt its organizational stability, resulting in a communication breakdown which would render its social intelligence useless. For example, removal of primary tumour followed by subsequent suppression of dormant metastases (secondary tumours) could be effective in preventing relapses. We need to study cancer as a whole, not as individual cells.

I implore you to read the original paper to truly understand cancer and its lethal intricacies.

Reference- “Bacterial survival strategies suggests rethinking cancer cooperativity”